Tama Ale Samoa • 12 February 2021

Tama Ale Samoa is the new Pouārahi Māori, leading intercultural strategy at the New Zealand Festival of the Arts. In his inaugural column about all things te ao Māori, Tama Ale brings us a Phrase of the Day - Kīwaha and a Short Story - Pūrākau poto about how the practice of tā moko came to be.

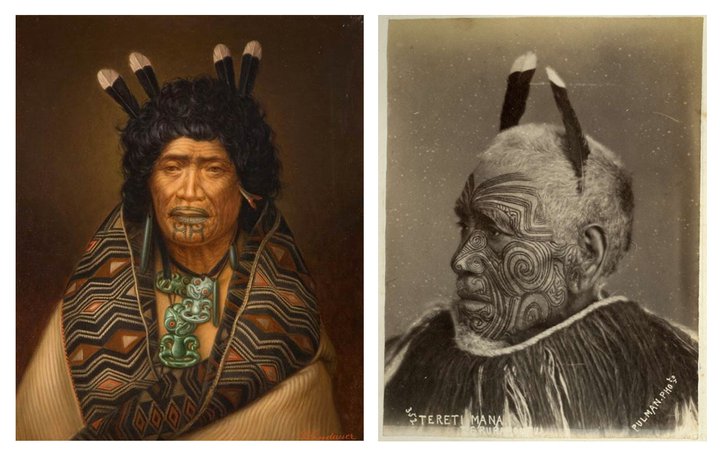

Te Rangi Topeora by Gottfried Lindauer via te Ara; Retimana Te Mania photographed by Pulman via the British Museum

Te Rangi Topeora by Gottfried Lindauer via te Ara; Retimana Te Mania photographed by Pulman via the British Museum

My name is Tama Ale. I was born and raised in Te Awa Kairangi, Lower Hutt. I am of Taranaki Māori and German Samoan decent and I have just started as Pouārahi Māori with Tāwhiri, New Zealand Festival of the Arts. My role here is to uplift the cultural capability within our organisation by integrating the Māori language and customs into our everyday operations. The ARTicle team and I have come up with an idea to have a segment in this article that soley focuses on things Māori, a place to share some general knowledge pertaining to the Māori language and customs, from introducing kapa haka, to learning new words and phrases.

Phrase of the Day / Kīwaha

Hei te tau tītoki (hay-tear-toe-tea-taw-key)

Iwi of origin: generically Māori

Difficulty: easy

Meaning: this phrase literally translates to “when the tītoki blooms.” The tītoki tree blooms at random, unlike other trees who have a certain season where they bloom, the tītoki can bloom at any time. So, it simply means, I’ll see you when I see you. If Shakespeare were here, he’d say something like “when the tītoki blooms, we shall meet again.”

Use: Only to be used if you don’t know when you will see the person again.

The tītoki berry. Image: Public Domain

Short story / Pūrākau poto

In precolonial New Zealand, otherwise known as Aotearoa, Māori chiefs had a unique way of identifying themselves, their skill set, social status, tribal affiliations and achievements. They did this using the art of tattooing or Tā moko. It’s the Māori form of identification; you could easily know a man by just viewing his moko. You can tell where in the ranks he stands, what his occupation is, whether he is the first born, his wives and children, his iwi affiliations, his prowess as a warrior or a priest and more. This type of moko was for males and is called a mataora.

Women had their own moko, known as the moko kauwae. The lips were the first to be tattooed, which was done when a young woman gave birth. Having children gave any woman the right to speak and have their say in all the iwi’s decision-making, hence the reason for tattooing the lips. Those of more seniority would have their chins tattooed, and the women who were involved in ritual and incantation would have their nostrils tattooed.

Through the nostrils of Tāne, the first human being was given life. That first human being was a woman, hence the reason why women hold such mana, and their moko represents the sources from where their mana derives. One, because they are the givers of life, and two, because they were the first to receive life.

As well as having deep meanings, the moko was also valued for its beauty, and is still used today as a way of enhancing our natural beauty. But more importantly today, it’s a way to show the world that we are Māori, and everything that being Māori stands for.